When I was studying music as a kid, just the word “intervals” would make me groan. “Ah, crap… I get it. It’s the distance between two notes. Whooooo cares!?”

But the longer I played, the more I realized that my sight reading skills and ability to understand the construction of a song all thoroughly depended on what I’d learned about intervals. The longer you play, and especially on guitar, the more you’ll think in terms of intervals than note names.

By the way, if you’re not yet familiar with how to read all the notes on your fretboard, that will help to give you an even better understanding of the stuff we’re talking about here. Check out my easy fretboard reading trick here.

So, what are intervals?

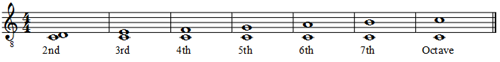

And how can you apply them to your guitar playing to make both reading notation and improvising easier? An interval is simply the distance from the starting note to the ending note. For instance, C to E is a distance of 3 notes (C-D-E) so it’s called a 3rd.

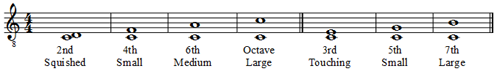

Here’s what each of our basic intervals looks like: (Need a quick refresher on how to read music notation?)

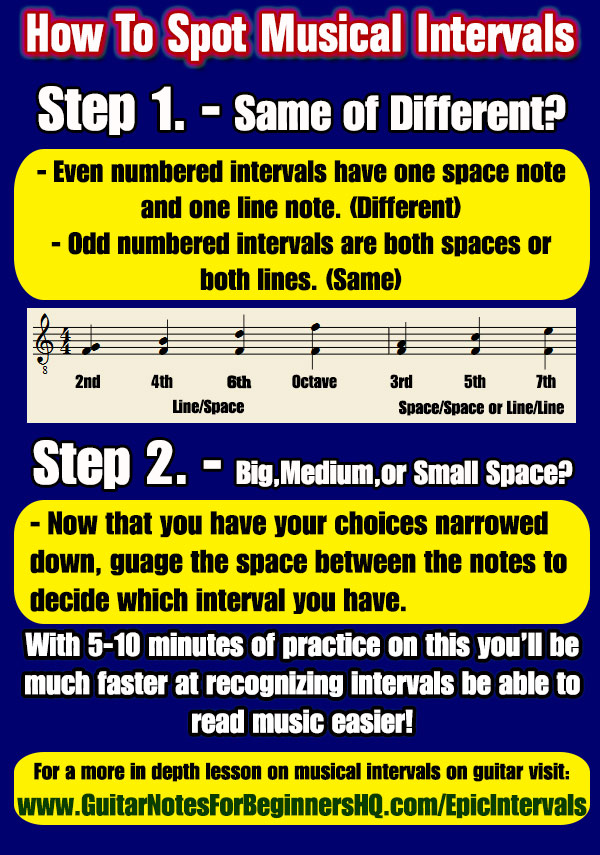

There’s a super easy, two-step trick for spotting these easily on a page.

Step 1: Decide if it’s an even or odd numbered interval.

Here’s how…

Take a look at all of the even numbered intervals. You’ll notice that one note is on the line, the other on the space. Now look at the odd numbered intervals. Both notes are either on the line or the space (line, in the case of the graphic above). Just check to see if the notes are the same (both lines or both spaces) or different (one line, one space) and you’ve immediately narrowed your choices down to 3 or 4 intervals.

Step 2: Decide on the right interval by looking at the gap between notes.

Here’s how…

It’s very easy to eyeball the size of the gap between notes once you’ve got them classified as even or odd intervals. To practice this, open up any sheet music you have lying around and start name the intervals between the notes. You can do this both with chords and with melodies by naming the distance between melody notes.

The next wrinkle is that some of these intervals have both major and minor versions. If you’re just reading notes from the page, this isn’t a problem at all. The sharps and flats will either be in the key signature, or right next to the note (called an “accidental”). Just figure out the correct letters (called a “pitch class”) and then slap the sharps and flats onto them as needed.

The next wrinkle is that some of these intervals have both major and minor versions. If you’re just reading notes from the page, this isn’t a problem at all. The sharps and flats will either be in the key signature, or right next to the note (called an “accidental”). Just figure out the correct letters (called a “pitch class”) and then slap the sharps and flats onto them as needed.

But if you’re trying to figure out the right notes for a chord or just have a need to find the right notes when they’re not written anywhere, you’ll need a better system for major and minor intervals. Let me first give you a tool that will cut that work in half….

What are reciprocal intervals?

This is a big name for a tiny idea. A reciprocal interval means you just flip the order of the notes. For instance C and F. If we start on C and go up to F we have a 4th. But if we flip them upside down, starting on F and going up to C, we have a 5th.

So what’s the trick? Subtract from 9 and flip the quality (major or minor). Super easy. Here’s another example. G and B. If we start on G and go up to B that’s a major 3rd (G – A – B). But if we start on B and go up to G we get a minor 6th (B – C – D – E – F – G).

Exercise: Figure out the reciprocal intervals for these examples:

1. major 2nd

2. major 3rd

3. perfect 4th

4. perfect 5th

5. minor 6th

6. minor 7th

(Answers: minor 7th, minor 6th, perfect 5th, perfect 4th, major 3rd, major 2nd)

Now that you know how reciprocal intervals work you can learn a system that only takes into account the first three intervals, then use reciprocals to find the others.

2nds – These are simple. A minor second is just a half step (one fret movement). A major second is a whole step (two frets movement)

3rds – The easiest way to deal with these is to count half steps. A minor 3rd is three half steps above your starting note. For instance, starting on G on your 1st string, go up 3 half steps (3 frets) and you’ll be at Bb, which is your minor 3rd. A major 3rd is one extra fret, four half steps higher from your starting note. Our previous example would put you on a B natural. You can, of course, put that note on a different string once you know what it is.

4ths – This is what’s called a “perfect interval” which means it doesn’t have major and minor variations. When you flip it, it becomes a perfect 5th. In a 4th both notes will be natural notes or both chromatic notes. For instance C and F, C# and F#, or Eb and Bb. The only exception is B and F# and Bb and F.

Remember, once you have your 2nds, 3rds, and 4ths you can easily use reciprocal intervals to find your 5ths, 6ths, and 7ths.

Ok, so how do we actually use these intervals on guitar?

Now, finally, how do we apply this with easy to remember patterns on the guitar neck? The good news is that if you have patterns for 3 of these intervals, the other 4 can be figured out on the fly very quickly. As always, memorize as few things as possible and let your brain work through the system to figure out the unknowns.

The 3 patterns you want to know are the 4th, 5th, and octave. They are both very simple shapes and very commonly used in the construction of chords.

These are moveable shapes and work anywhere on the neck and on any pair of strings EXCEPT the 2nd and 3rd strings. I’ll show you how to tweak them to work there too.

These are moveable shapes and work anywhere on the neck and on any pair of strings EXCEPT the 2nd and 3rd strings. I’ll show you how to tweak them to work there too.

Once you have these, we can use a teeny bit of logic to find the other intervals. For instance, if a 3rd is smaller than a 4th, then we can move that 4 down a fret to get a 3rd. The same goes for 6ths and 7ths based on the octave pattern.

Check out the graphic below. The gray dots are the basic 4th, 5th, and octave intervals from above. The red dots show you how to find all your 2nds, 3rds, 6ths, and 7ths by referencing the previous patterns.

As with the others, all of the patterns are moveable to any set of strings, though they change a little when you reach the 2nd string. More to come on that.

For right now, practice these patterns on your bottom three strings. Get used to first referencing your basic 4th, 5th, or octave pattern, then thinking from there to get the interval you’re looking for.

Darn you, pesky 2nd string!

I’m sure you’re aware that, in standard tuning, the interval between the open 2nd and 3rd strings is only a 3rd (G to B) rather than a 4th like all the others. If it weren’t this way, all our fingerings would be so stretched out they’d be nearly impossible to play. The trade off is that we have to make some adjustments to our patterns when we encounter the 2nd/3rd string area.

Mostly it will involve moving the top note up just one fret to adjust our stock patterns. Here’s what to look for:

3rd and 2nd string – Move the 2nd string note up one fret.

3rd and 1st string – Move the 1st string note up one fret.

2nd and 1st string – All your normal patterns work again.

Not too difficult, eh?

Of course, these are not the only way to play these intervals. But they are a good starting point. Get comfortable with these first, then start hunting up some others.

To Come Full Circle… What’s the point?

As I mentioned early in the article, your notation reading skills will quickly come to rely on intervals to move through the music faster than reading one note at a time. Now that you have patterns you’ll be able to read that interval and go straight to your pattern without having to hunt around the neck for a note. It will take a little bit of practice to trust your own head to give you the right answers.

In a more subtle fashion, knowing how intervals work on guitar will improve your phrasing. See, the music is created in the relationships between the notes, not the notes themselves. One note means nothing. Two notes starts to lead your ear in a particular direction. So by reading the relationships of the notes rather than each note in a vacuum, your brain will be attuned to the way the notes work together to make the music. It’s the kind of tiny tweak that can lend a cohesiveness to your playing that you didn’t have before.

I understand that there is a TON of information here. Even though this is supposed to be “intervals for beginning guitar”. So don’t feel bad if you don’t completely get it all the first time. Work with one section at a time until you get comfortable with it. Then add the next skill. And please feel free to leave me a comment if you have any questions.

And if you’d like more instruction on using intervals to help you master scales, I absolutely recommend Guitar Scale Mastery.

Here’s your cheat sheet!

How to buy a guitar for someone else…

Get my guide to the “12 Parts of Playing Guitar You Need To Know” plus “The Perfect Practice Session” by sending out a quick tweet with the Tweet2Download button below.

12GuitarThingsPerfectPrac ..

What a great lesson, such concepts are hard to find around the Internet, with all the information scattered everywhere. Thank you for being so awesome!

Glad you found it helpful Georgi. 🙂

Excellent article. No one ever pointed out the same/different close/far thing for quickly identifying intervals written in standard notation. Also I’d never heard of the idea of reciprocal intervals, never understood why “perfect” without that notion. Finally on your cheatsheet I might mention on Step 1 between the text “4th” and “Octave” you have “4th” printed 2X, the second one might have been intended to be “6th”.

Thanks James. I’m glad you found this useful. Usually if I look at how I use stuff in the real world in my own head, I run across and easier way to explain it. And thanks for pointing out the screwup in the cheat sheet too. I hadn’t noticed that. You’re right, the 2nd one should be a 6th. I’ll fix that.

hi

i’m a little unsure about the approach you use. i’m starting to think now that I only need to identify the type and not quality (eg minor or major), and from there on the fly just pick the interval that falls on the natural (it could end up being a maj 6th, or a minor 6th). initially i thought we had to be able to identify the quality (major or minor) on the fly while reading the score, but that is not true i take it then? you’re approach here is not to do that but pick the natural note as on the staff to finalize the interval type (maj or min). am i right?

to clarify, what i mean is that eg. i know where the 6th interval note falls (one of 2 locations). i just pick the natural location. and if there are accidentals i modify accordingly.

Hi Jo… Sorry to take so long to reply. Yesterday was a travel day on tour. 🙂 Yes, you’re essentially correct. Once you’ve got the interval, you can quickly modify the natural notes based on the key signature or accidentals. From a note reading perspective, that takes care of majors and minors for you.

From an ear training perspective it’s definitely important to be able to pick out your major and minor intervals. But that’s a bit outside the scope of this lesson.

Thanks for responding, but i’m not 100 sure. I’d like extra confirmation, if you don’t mind. for example, i see the bottom note on the score, and it’s a D. I also see the interval on the score and it’s a 6th (ie. a 6th interval between the D note and the other top note i must play at the same time). i then on the fly play the D and the other note picking one of 2 possible locations on the fretboard for the other note , going for the natural note location. correct? or should we be learning to identify whether the interval is maj or minor just by looking at it on the staff (ignore accidentals for this example)? this would be faster but involve learning more configurations off memory. specifically, we would have to learn to sight both the size of the interval and it’s type.

I always try to look for ways to keep memorization to a minimum. Our brains don’t work that great with memorization. But were are fantastic with systems. So rather than creating additional memorization points, it’s better to let your brain work through the steps. And that will happen faster with practice.

So in this case, there are two steps. One is picking the interval and it’s two possibilities as you mentioned. The second step is seeing if the note needs to be changed to a sharp or flat based on either the key signature or the accidental. We can’t ignore accidentals because that’s what will change the quality.

As you play and gain experience, you’ll naturally start to memorize the quality of the intervals on site. That can happen through repetition (in the context of actual pieces) much more easily than forcing yourself to memorize them.

I hope I’m understanding your question correctly.

thank you for taking the time to answer my question. This is a great article on the Internet, as there really isn’t much out there on this topic. I should be fine now. My original understanding was correct.

Glad to help man. 🙂

Along the way I learned to read an intervals type (number) from standard notation by starting from the lowest note and counting the lines and spaces to the higher note. Let’s start with the 6th and 5th strings at the fifth position, A to D = perfect fourth. Now play starting at the 5th to the 6th string fifth position, D to A = is this a perfect 4th or a perfect 5th?

You’re correct of both accounts, Scott. It’s what’s called a “reciprocal interval”. You can find them for all the other intervals with a simple formula: Subtract from 9 and flip the quality.

For instance: A major 2nd (C-d) becomes a minor 7th (D-C). Or a minor 3rd (C-Eb) becomes a major 6th (Eb-C).

The perfect intervals stay perfect (how nice for them…) and so your example of A and D is correct. If just depends on which note you put on the bottom.